Authors: Lucia Garrido, Blanca Casares, Roxana Vilcu, Youna Deniaud, Miranda Garcia (AEIDL)

The EU Rural Digitalisation Forum (RDF), set-up by the DESIRA (Digitisation: Economic and Social Impacts in Rural Areas) project, held the first part of the second meeting online on 7 December 2021. The RDF is a platform that brings together a wide range of stakeholders working on the digitalisation of rural areas. It aims to be a space for sharing experiences, ideas and recommendations, and communicating them across Europe.

This second RDF meeting brings together 30 participants from different backgrounds (research, public authorities, SMEs, stakeholders’ organisations, members of National Rural Networks) to develop linkages between the DESIRA Living Lab scenarios up to 2031 and the Long-Term Vision for rural areas in 2040.

During this first part, participants discussed about how could digitalisation impact the long term vision for rural areas. For that, they were spread across four breakout rooms, structured around the long-term vision action areas.

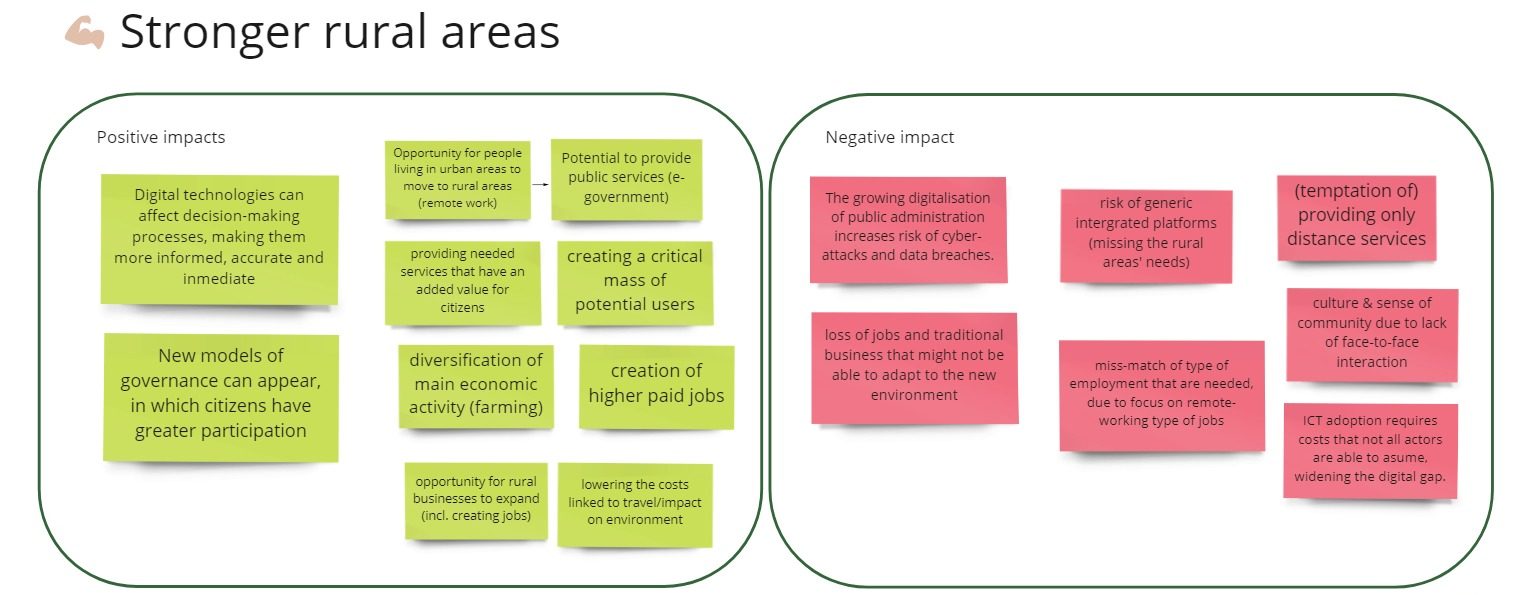

Stronger rural areas

Stronger rural areas within the LTVRA refers to focusing on empowering rural communities, improving access to services and facilitating social innovation. One of the most important aspects in which digitalisation could be a game-changer for rural areas raised in the discussion was e-governance. Rural areas face weaknesses of the administration and a lack of services provision. In this regard, digitalisation can change the situation. Putting together municipalities to join forces, using existing software and procedures, can fulfil the gap of the distance.

Another point mentioned is broadband penetration, which is increasing and is opening opportunities. This has led to a cultural shift in rural areas, adapting to using new means of communication. But there is a big gap in terms of skillset in many rural communities. Skills uptake has not been happening at the same speed as broadband roll-out. This means fewer people using also the services that are being offered. There is a need to understand what services are viable in the different rural communities. The public sector is driving it in many countries, yet services have been provided in different ways across rural areas. For example, in Ireland, a lot of services have been centralised, but easy online access has lowered the burden of administrative procedures, enabling it to do so remotely.

Stronger rural areas are those where municipalities have a voice in the national context, can pursue their own political agenda. A centralised government with less representation of rural areas in the Parliament makes them dependent on the central government. Stronger rural areas have decentralised policy-making and autonomy.

Lastly, participants pointed out one of the positive effects of the COVID pandemic: urban people moving to rural areas. Stronger rural areas are perceived as nice to live in, with increased well-being. In turn, it led to several problems, i.e. housing, which should be addressed at the policy level. In terms of services and platforms, we should try to combine them and integrate them across sectors to increase their attractiveness (cross-sectoral), promoting attractive business models in the data economy.

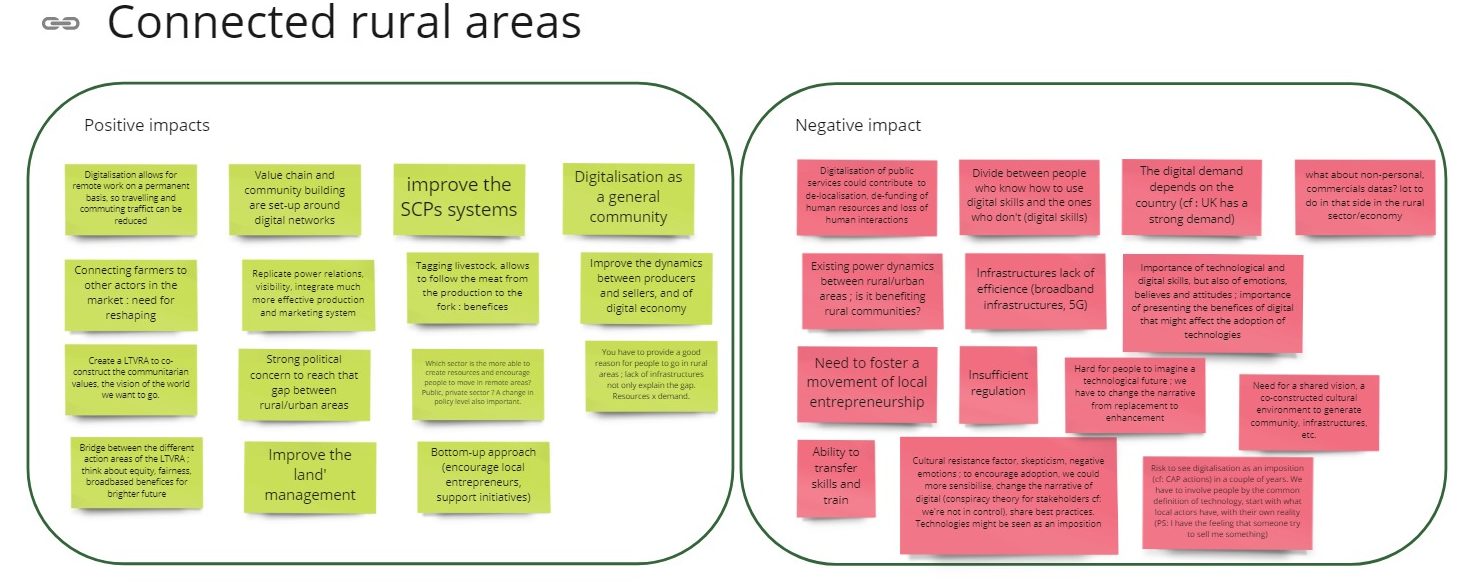

Connected rural areas

Connected rural areas within the LTVRA refer to them being well connected between each other and to peri-urban and urban areas. On the one hand, in terms of positive impacts, one of the most evoked arguments in support of digitalisation in rural areas is the possibility of creating new market dynamics through the development of better production techniques – such as livestock tagging, and better information transmitted to the consumer, which allows the valorisation of farm products, the connection of farmers with the different market actors, the improvement of the dynamics between producers and sellers, and the development of the digital economy. The community aspect was also one of the most mentioned points since the constitution of a digital network allows to co-construct a vision of the future that is coherent with the LTVRA. It makes the link between the different action areas of the latter, but it also enhances the valorisation of the value chains, as well as develops and welds the SCP systems. It is also important to underline that the use of digital technologies would to some extent bridge the gap between urban and rural areas, and that travelling and commuting traffic can be reduced through remote work

On the other hand, several points were made about the likely negative impact of digitalisation in connected rural areas. The major opposition to this is the form of cultural resistance to the implementation of a technological future; indeed, local people may see this as an imposition, a form of replacement of traditional knowledge which can be seen as a threat of corporations – for example, there is a fear of delocalisation, defunding of human resources and the loss of human interests through the digitalisation of public services. The experts agreed on the importance of emotions and the construction of a new narrative to transform this cultural resistance. It is also important to remember that there is a divide in the population in terms of digital skills; reconfiguring the power relations between urban and rural areas, as well as putting in place training on digital technologies accessible to all would allow this gap to be filled. We can therefore see that the lack of efficiency of technological infrastructures is not the only factor explaining the gap, and that we should sensibilise people to the opportunities offered by digitalisation as a means, not an end.

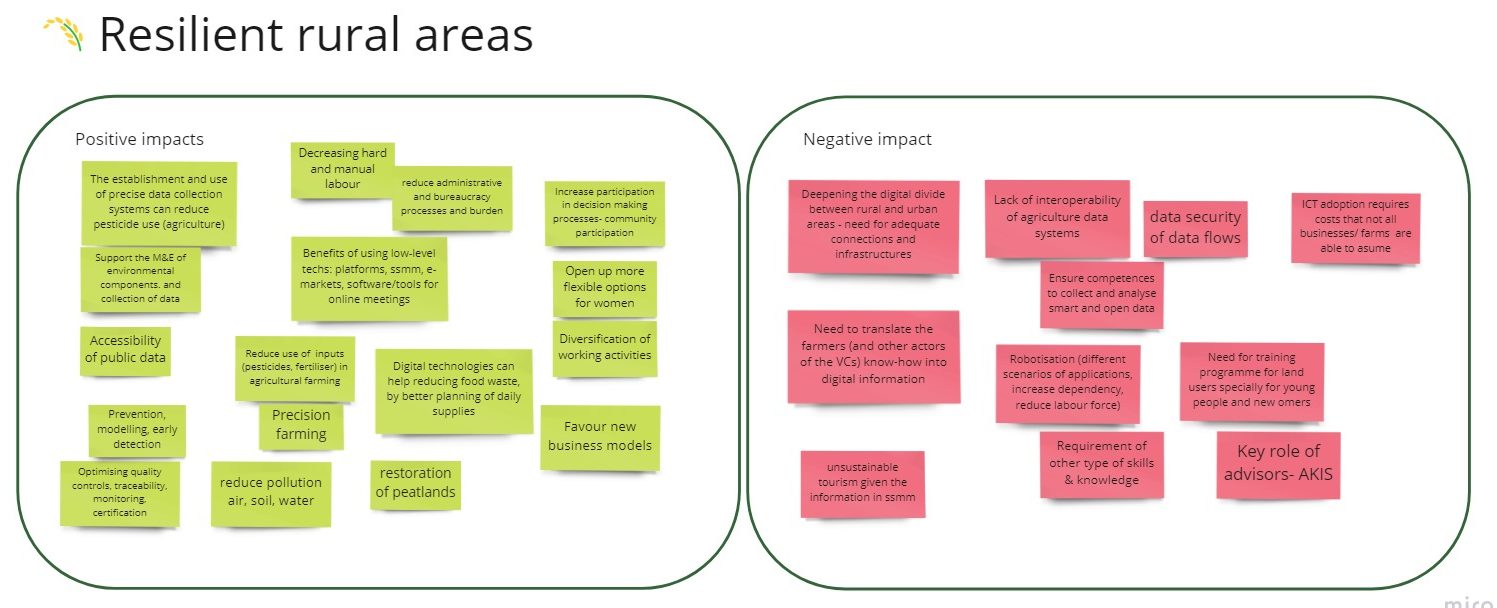

Resilient rural areas

When talking about more resilient rural areas, the LTVRA refers to the preservation of natural resources, the restoration of landscapes, including cultural ones, the greening of farming activities and shortening supply chains. Within the RDF meeting, participants noted how the establishment and use of accurate monitoring and evaluation data systems can reduce the use of inputs in agriculture (fertilisers, pesticides, antimicrobials). Such precision farming will reduce air, soil and water pollution. In addition, from an environmental point of view, digital technologies can help reduce food waste, through better planning of daily supplies as well as peatland restoration. Digitalisation also facilitates prevention, modelling, early detection, optimisation of quality controls, traceability, monitoring, certification in agriculture, livestock and forestry management which reduces environmental risks.

Digitisation can lead to a reduction of hard and manual work and a reduction of administrative and bureaucratic processes. At the social level, digitalisation will favour participation in decision-making processes. It will open up new, more flexible labour options for women, diversifying work activities and favouring new business models. It is important to note the positive benefits of using low-level technologies such as platforms, social media, e-marketplaces, or software/tools for online meetings.

In terms of potential negative impacts, there may be a deepening of the digital divide between rural and urban areas, so there is a need to ensure adequate connections and infrastructure. There is a risk of a lack of interoperability of agricultural data systems and security of data use. At the users’ competence level, other skills and knowledge will be needed. It is therefore important to focus on training programmes for land users, especially for young people and newcomers. In addition, advisors will play a key role, as well as AKIS. It is also necessary to capitalise on the knowledge of farmers, and other actors in the value chain, by translating their know-how into digital information. Robotisation cannot be applied in all scenarios, as it could increase dependency and reduce labour. The adoption of ICT requires costs that not all companies or farms can afford.

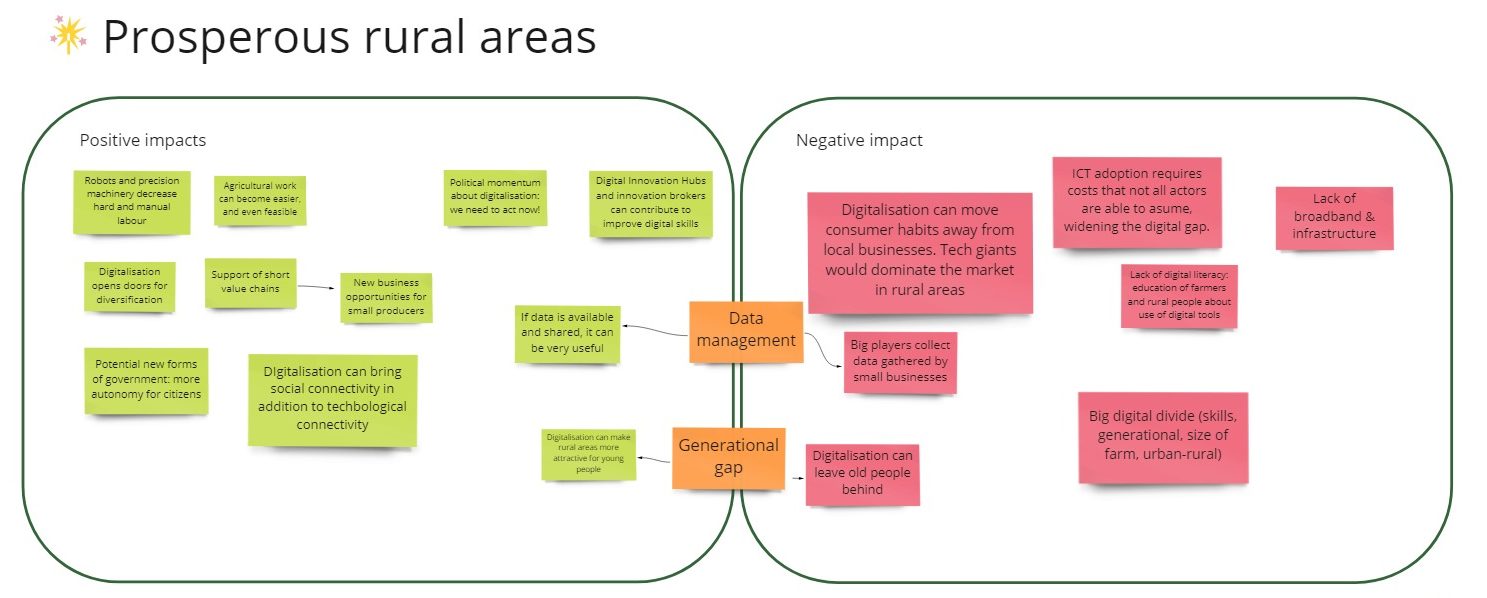

Prosperous rural areas

Prosperous rural areas refers to diversifying economic activities to new sectors with positive effects on employment and improving the value-added of farming and agri-food activities. In this sense, participants of the RDF noted that we are experiencing a momentum for digitalisation that we must seize now. The use of robots and other devices could help decrease hard and manual labour, making agricultural activities not only more attractive, but also feasible in areas severely affected by climate change. However, ICT adoption requires costs that not all actors are able to assume, widening the digital gap. The lack of broadband and infrastructure in rural areas does not help either.

Digitalisation also can bring social connectivity in the means of diversification, as it can support the development of short value chains, and open the market for new business opportunities, which is a great advantage, especially for small producers. However, tech giants could dominate the market in rural areas if they move consumer habits away from local businesses. Digital literacy is also key. There is a strong need to educate farmers and rural people about the use of digital tools and the benefits they could bring. Digital Innovation Hubs and advisory services will have an important role in this sense, as they could contribute to improving digital skills. Even if digitalisation can make rural areas more attractive for young people, it poses a big risk of leaving old people behind. The digital transformation should take everyone into account, so the development of human skills is as important as infrastructure or broadband deployment.

Finally, another issue that should be taken into account is data governance. Having access to data can be a huge game-changer for rural people. However, at the moment, the ones that are able to collect and process the data coming from rural areas are the big players.

Other presentations

In addition, the event counted with several presentations from high-level experts.

Alexia Rouby (DG AGRI, European Commission), introduced the EU policy context by presenting the long-term vision for rural areas, and how it is articulated (see video, presentation). Maciej Krzysztofowicz, from the Joint Research Centre, presented the foresight exercise developed by the JRC in collaboration with the ENRD’s thematic group, that contributed to the long-term vision (see video, presentation). Finally, Sabrina Arcuri from the University of Pisa explained the work developed by the H20202 project SHERPA, regarding an overview of foresight and scenario studies at the EU level (see video, presentation).

Coming from DESIRA, participants could hear Dominic Duckett, from the James Hutton Institute, introducing the EU-level foresight carried out by the project (video, presentation), and the scenarios emerging from two of our Living Labs: the Latvian case, presented by Mikelis Grivins from the Baltic Studies Centre (video), and the Scottish case, presented by Leanne Townsend, form the James Hutton Institute (video, presentation)